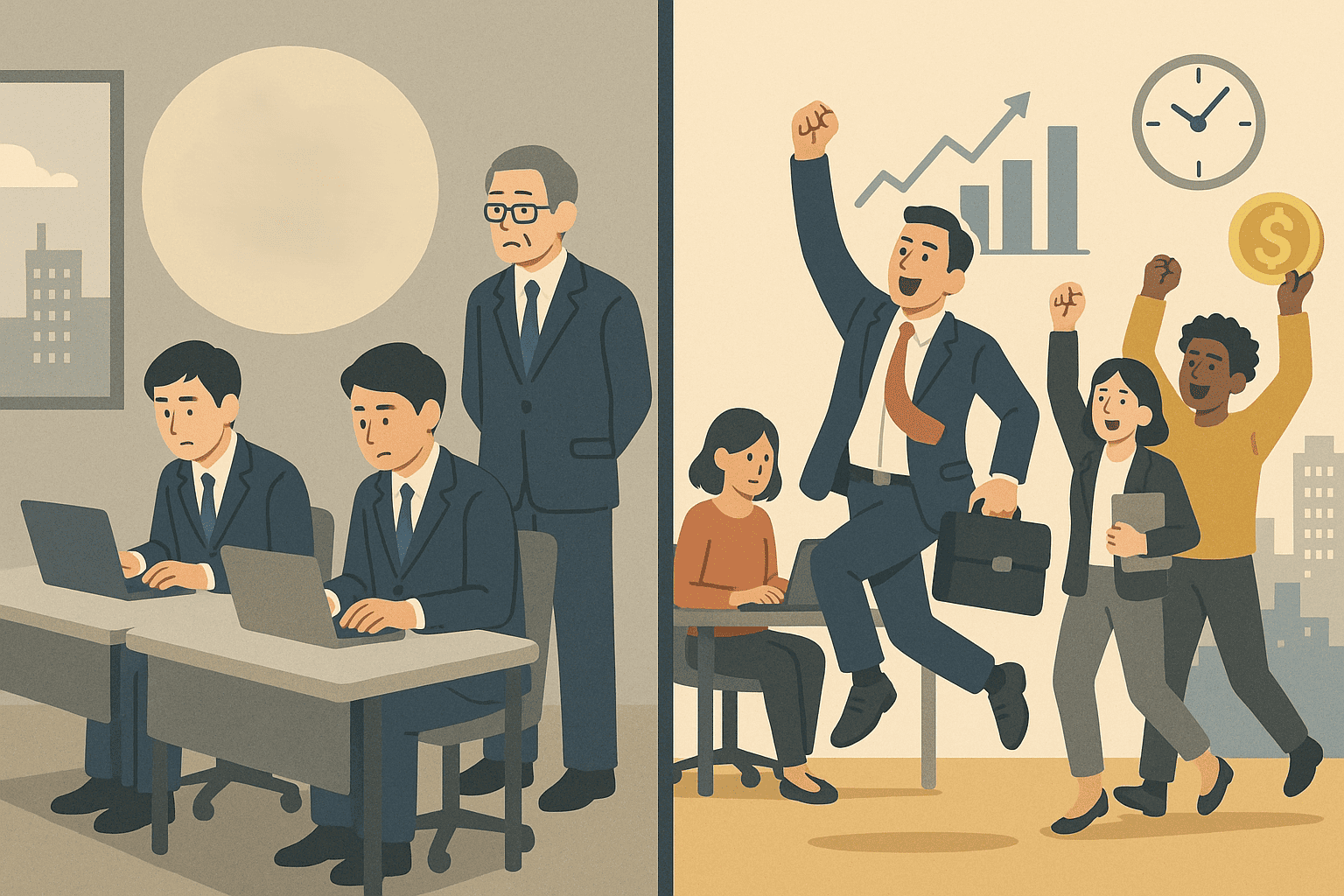

As the role of Japanese companies in Taiwan shifts—from traditionally being offshore manufacturing hubs to evolving into service-oriented, market-driven, and regional operational centers—their talent strategies are now facing structural challenges. In recent years, the attractiveness of Japanese firms to Taiwanese talent has gradually declined, not merely due to decreasing salary competitiveness, but also because their organizational culture and governance models have lagged behind the pace of change in Taiwan’s workplace environment.

With the new generation of workers no longer viewing "stability" as a primary workplace value, many of the management practices long taken for granted by Japanese companies are becoming increasingly out of sync with local workplace expectations, making talent management a critical threshold for the continued deepening of Japanese business presence in Taiwan.

1. The appeal of the employer brand is fading

Japanese companies in Taiwan were once regarded as paragons of stable employment. For many job seekers, joining a Japanese firm meant access to a well-established system, disciplined management, and solid training opportunities. However, such an employer brand advantage has gradually diminished in the eyes of the younger generation. Generation Z and young professionals are more concerned with factors like growth potential, learning opportunities, career transparency, and an open organizational culture.

In contrast, the traditional seniority-based system, lifetime employment culture, and collective decision-making mechanisms of Japanese companies now appear sluggish when compared to the flexible, self-driven career logic that prevails today. The appeal of Japanese firms has notably declined—especially when Western multinationals and startups offer high-challenge, high-reward environments. For mid- to high-potential talent with language skills and international experience, the willingness to join Japanese companies has been decreasing year by year.

Moreover, this decline in attractiveness cannot be offset merely by brand legacy or company size. In the digital era, employer branding is no longer defined by past prestige, but by actual employee experience, institutional design, and cultural fit. Without proactive transformation, Japanese firms risk losing ground in an increasingly competitive talent market.

Image source:AI

Image source:AI2. The Limits of Transplanted Management Models

Many Japanese companies in Taiwan still rely on their headquarters to dictate institutional design and HR policies, including compensation structures, job rotation systems, promotion processes, and performance evaluation standards. While this direct transfer of Japan-based management frameworks has proven effective domestically, it often leads to significant friction in the Taiwanese workplace environment.

One of the most apparent issues lies in the mismatch between decision-making speed and accountability. Japanese firms tend to prioritize consensus and risk minimization, which often results in lengthy internal approval processes and overly centralized authority. For Taiwanese employees, such a model can slow down execution and diminish their sense of ownership and achievement. In some companies, the local teams are responsible for implementation, yet ultimate decision-making power remains with Japanese managers—creating a structural contradiction that undermines communication efficiency and organizational trust.

Another challenge stems from cultural differences in communication. Japanese-style communication emphasizes subtlety, indirectness, and avoiding confrontation—often described as “reading the air.” In contrast, Taiwanese workplaces increasingly value direct feedback, collaborative discussion, and individual expression. Without mutual adaptation and redesign of communication norms, these differences can easily lead to misunderstandings, misjudgments, or internal friction—especially in cross-functional or multilingual settings.

When systems are exported without cultural recalibration, misalignment only becomes more entrenched. This suggests that localization is not merely about tweaking processes, but about rethinking how organizational culture can truly enable meaningful participation from local talent.

3. The Fracture in Employee Experience

When companies fail to promptly adjust their talent governance strategies, the most immediate impact is often seen in employee retention and organizational climate. Observations of Taiwan’s broader labor market show that companies are generally facing increasing turnover among mid- to high-potential talent. For Japanese firms, which tend to prioritize stability as a core management principle, such a trend creates added pressure in terms of talent gaps and disruptions in internal development pipelines.

This trend reflects a breakdown in the "psychological contract"—when employees' expectations toward the company are unmet, they become less willing to commit long-term. Compared to Western firms that emphasize flexibility and challenge-driven careers, many Japanese companies still rely on stable employment relationships, internal promotion systems, and uniform benefit packages as their main tools for attracting and retaining talent. However, such systems often fall short in addressing what younger generations now value in the workplace, and they tend to overlook three key dimensions of employee experience:

- Whether the management style allows employees to express opinions and challenge processes

- Whether career paths are transparent and opportunities for learning are accessible

- Whether flexible work arrangements, emotional support, and a sense of purpose are present

When these needs are not met, even competitive pay and complete systems may not be enough to prevent employees from leaving for workplaces that offer greater cultural compatibility and personal growth opportunities.

4. The Adaptation Challenge under a Generational Gap in Japanese Management

Although some companies have recognized the need to localize their talent systems, the actual effectiveness of such efforts remains limited. A frequently overlooked issue is that Japanese companies in Taiwan still heavily rely on Japanese expatriate managers to lead governance and decision-making. These managers are often in their 50s or older, with long service histories at the headquarters. While they are well-versed in the operational norms of Japan and have extensive internal promotion experience, they often lack a deep understanding of Taiwan’s labor market logic, managerial context, and the characteristics of younger talent.

This management structure requires local branches to follow headquarters’ processes institutionally, and to replicate Japanese operational logic culturally—yet these often clash with local realities. For example, expectations around reporting formats, promotion evaluations, or personnel rotations are frequently detached from local business conditions, leading Taiwanese employees to feel a lack of participation and recognition.

Notably, when Taiwanese junior staff express opinions or propose improvements to systems, some Japanese managers may interpret these actions through a Japanese workplace lens, where such behavior might be viewed as lacking maturity or loyalty. These cultural mismatches can occasionally lead to misinterpretation of intent, affecting communication efficiency and mutual trust. Generational and cross-cultural differences in perception are long-term challenges that international organizations must actively manage. When addressed through institutional design and cultural development mechanisms, they can help foster internal alignment and accelerate transformation.

Ultimately, before discussing innovation or structural reform, companies must first consider whether they are willing to reevaluate and reconstruct their internal governance models—providing local teams with real authority and space to participate. Without this, even the most sophisticated performance systems or talent policies may fail under a closed decision-making regime.

5. The Next Step for Japanese Companies in Taiwan — Rebuilding the Social Contract with Talent

For Japanese companies to deepen their presence in Taiwan, the challenges they face go beyond language or cultural adaptation. What’s at stake is a broader shift in governance logic and talent philosophy. In an era where workplace values are evolving rapidly, stability and structure still have their place—but they must be balanced with greater flexibility and a deeper understanding of local contexts.

Localization should not be limited to surface-level adjustments in policy. Rather, it is an opportunity to reexamine the relationship between people and organizations. When companies are able to view talent as co-creators, and strike a new balance between culture and system, the role of Japanese firms in Taiwan can move beyond that of a satellite operation, becoming a dynamic platform for meaningful collaboration and sustainable growth.